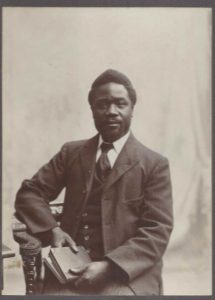

Mantantu Dundulu, N’lemvo. Linguist, pioneer, man of faith.

Posted Friday, 9th October 2020

To celebrate Black History Month, Dr Daniel Gerrard , Lecturer in Medieval History here at Regent’s, is jumping ahead a few centuries from the Middle Ages to write about an amazing man, Mantantu Dundulu, better known as N’lemvo. A superb linguist, interpretor ,translator and possibly the first Christian Protestant convert in Congo, here he commemorates his remarkable life.

In Ngombe-Lutete (Congo) stands a memorial plaque and bust to one of the outstanding figures of early twentieth century African Christianity and linguistics, Mantantu Dundulu N’lemvo. The memorial depicts a dignified, elderly gentleman, his blind eyes hidden behind dark glasses, recalling him as Premier Chrétien Protestant and Batisseur de l’Eglise du Christ au Congo. In a period where much controversy surrounds who and what is commemorated in statue form, we are glad to have the focus in Black History Month on a remarkable man whose contribution was not outweighed by inhumanity but was instead elevated by his commitment to the care and enlightenment of others.

Early Childhood

N’lemvo was born near San Salvador in what was then the Kingdom of Kongo, a vassal state of Portugal, around 1870.1 Many of the details of his early life are disputed or uncertain in our sources, including his unusual collection of names. ‘Dundulu’ means ‘stupid’, a moniker that those who knew him believed he had acquired, either through refusing to admit that he could ‘see’ the spirits of his ancestors at an initiation ceremony, or because he was apparently uninterested in embracing the tenets of Catholicism.2 The ‘Mantatu’ name has a darker story behind it, though an equally uncertain one. N’lemvo himself wrote that he was separated from his father when his father and uncle quarrelled over money, leading to a division of the family’s children.3 A somewhat more lurid story, but one attributed to N’Lemvo, that appeared in Quest after his death, reported that N’lemvo’s father died on the day of his birth, and that his father’ brother and sister were both suspected of witchcraft and killed.4 What is not in dispute is that his early life was marked by tragedy, and that his mother gave him the name ‘Matantu’ (‘Ntantu’ means ‘sorrow’) and he was brought up in the care of his uncle, Tulante Mbidi. N’lemvo left a vivid account of a challenging childhood with his uncle, taking responsibility for the care of siblings, catching eels with his uncle, and trading chickens for strings of beads. He even sought work as a labourer at the age of nine, but was regarded as too young to be effective in that role.5

On 29th April 1881, he was brought by a Catholic priest6 to meet the British missionary and linguist, Dr Holman Bentley, who immediately became both his teacher and his employer.7 It was Bentley who gave him the name N’lemvo, for his birthplace of Lemvo, which also means ‘obedience’, a name that apparently suited the gentle personality of the boy very well.8

Education

N’lemvo’s meeting with Bentley was a decisive event in the life of both men. In time, N’lemvo would become enormously important to Bentley’s linguistic work as well as his evangelism, but there were stumbling blocks along the way. N’lemvo was initially worried that at least some of Bentley’s acquaintances might be cannibals! He was afraid on his first encounters with the written word, though quickly mastered the alphabet, the basics of English pronunciation, and was able to begin moving on to a more advanced level of education.9 He also quickly began to express interest in converting to Christianity, telling Bentley of his ‘personal trust in Christ’ by 1882.10

Travel

The Bentleys brought N’lemvo to Britain three times. His first visit had him arrive on 23rd March 1884.11 His second visit, had him arrive in April 1892.12 His third visit extended from 1904-1907.13 Though Dr Bentley viewed these visits as primarily an opportunity to focus on his linguistic work, and in particular of seeing publications through to press, these visits, which went via Normandy and Holland at least once, were also important educational opportunities for N’lemvo. He was taken to see the medieval remains at Caen,14 addressed the Pekela church congregation at Rotterdam (with translation helped by Mrs Bentley),15 and showed interest in a huge range of north-western European cultural idiosyncrasies, from glass blowing and peat cutting, to the practice of men engaging in agriculture.16 He was present at the Bentleys’ wedding, and wrote home of the strange custom of European ladies marrying while wearing mosquito curtains (i.e. wedding veils) over their heads!17 His own recollections of his first visit in particular are full of energetic enthusiasm for a trip to a coal mine and to Windsor Castle. Though disappointed that he did not have the opportunity to meet Queen Victoria in person, an enterprising member of the castle staff gave him a plate of Jelly and told him that he was eating the queen’s leftovers, which he happily and excitedly reported back.18

Linguistic Work

It is clear that the young N’lemvo was a precocious linguist. Though he had only begun to learn to read in 1881, by 1884 he was already at work with Bentley on what became the Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language.19 Bentley acknowledged the importance of precise local linguistic knowledge in both aspects of his own work:

A superficial knowledge of a language may suffice the trader, or explorer; but a very deep and thorough acquaintance should be sought by those who seek to inculcate religious truth, and to translate the Word of God.20

We might express a reservation that Bentley did not directly acknowledge N’lemvo’s support in his preface, but the frontispiece of the volume does have a photograph of Bentley, his wife (also much involved in translation work), and a young man who can only have been N’lemvo. Indeed, Bentley’s wife was keen in her own recollections to emphasise the importance of N’lemvo’s contribution:

While we were home on furlough in 1898 my husband succeeded in passing through the press, the Congo Grammar, Appendix of the Dictionary, and Congo Testament, every word of which had been subjected to Nlemvo’s keen criticism, who had been his helper in the language from the very first, and knew English well enough through having been to England three times and studied the language very carefully.21

In 1893, N’lemvo published his own translation of the book of children’s religious instruction, The Peep of Day.22 After their second trip to England, in 1893, Bentley and N’lemvo completed work on the translation into Kongo of the New Testament.23 These are the works for which he is most famous, but it is clear that he made contributions to a much wider array of work than is generally recognised. He supported Mrs Bentley’s work on a Harmony of the Four Gospels,24 and her assembly of a vocabulary of four languages (Congo, French, Portuguese and English),25 and her ‘History of the Israelites’.26 Even in old age, having lost his eyesight many years prior, he was still working with Rev. W.B. Frame on a new translation of the New Testament , and with R.L. Jennings on a translation of Stalker’s Life of St Paul.27

Christian Life and Evangelism

N’lemvo may have taken communion as early as January 1885, in England but he returned home to Congo for his baptism at Wathen on February 19th 1888.28 In 1889, he became one of the founders of the Wathen church.29 He was immediately made Deacon and Treasurer, and became superintendent of evangelical work.30 He himself built the first brick chapel at Nionga.31 His local connections into clan leadership helped his own evangelism to gain a popular hearing, and he was soon gathering small crowds at the nearby town of Vunda on Sundays.32 In July 1905, he was asked to speak on behalf of the Congo churches at the Baptist Congress at Exeter Hall. By that point, he was able to speak not only of his own joy in his conversion, but also of the conversion of nine or ten thousand of his countrymen.33 Contemporaries were clear that the dramatic successes of conversion in these years owed a

great deal to his ‘persistent enthusiasm’34. By his death in 1938, the number of converts may have grown to as many as two hundred thousand.35

Caring Roles and Supporting the Community

Though his linguistic and evangelical work constitute the core of N’lemvo’s historical legacy, it is clear that he made an incredibly broad range of contributions to his community in life. Often we find traces of him in caring or nursing roles, as when he supported Bentley during the latter’s period of failed eyesight,36 when he distributed vaccines at Vunda during a Samallpox outbreak,37 or when he rushed back to be at the bedside of his dying mother.38 We find him assisting in an operation to remove a girl’s eye,39 nursing a Medal Chief,40 building roads to help speed local traffic,41 hunting to bring his community food during a meat shortage,42 and dramatically saving at least two lives, one of a young man accused of witchcraft43 and another during a leopard attack.44

N’lemvo’s position as a convert did not make his relationships with his own countrymen easy. Though he inherited a chieftainship from his uncle, his Christianity was not compatible with the role, which he surrendered to another uncle.45 Proving that his religious affiliation had not broken his bonds with the community took time and effort. The lavish funeral that he conducted for his mother seems to have helped convince many that he was respectable,46 and over time we find growing evidence of his status as a community leader, especially in the resolution of local disputes.47

Personal Life and Relationships

N’lemvo’s correspondence, and the recollections of those that knew him, emphasise strongly his friendships and his wide range of personal interests. When they first met, Dr Bentley was not always certain how best to develop that relationship, whether as N’lemvo’s employer or in loco parentis,48 and it is clear that his upbringing of N’lemvo involved some corporal punishment, as was usual in parenting in the period.49 Nevertheless, his close friendship with the Bentleys is attested in many places. He felt the loss of Dr Bentley very keenly,50 and wrote with joy at the erection of a memorial plaque at Kibentele to his old friend’s life and work.51 In his correspondence with Mrs Bentley, the deep affection between the two can hardly be missed. Even in his old age, he described himself as her ‘child’.52

We know less about his family relationships, though these were clearly deeply important to him. He married twice, the first time to Kalombo in 1888.53 Kalombo had been captured by Arab raiders and forced into slavery, but was rescued and brought to the Mission station, where she and N’lemvo met.54 Kalombo died on 13th November 1898 after a long illness, and N’lemvo married again three years later (though our sources are silent as to the identity of his second wife, beyond that she came from the Katanga region.55 Although N’lemvo’s life was yet again marked by tragedy, when his eldest son, Kikudi was killed choking on a fishbone in 1893,56 he took great joy in his growing family. By the time of his death he had at least eleven grandchildren.57

N’Lemvo’s particular interest in and care of children is a theme that runs through our sources for his life,58 beginning in his own childhood, when he was responsible for caring for his sisters. He vowed that his own children would never be separated as he had been from some of his siblings,59 and it is striking that in his correspondence with Mrs Bentley he shows particular interest in how the legacy of her translation work was contributing to children’s education in French several decades later.60 It is characteristic of this interest and care that after he lost his sight, N’lemvo took the opportunity of a young British girl reading the New Testament to him to gently begin her own education in scripture.61

Blindness

N’Lemvo spent the last three decades of his life blind. Since he began to encounter serious difficulties with his vision on one of his trips to England, a number of contemporaries attributed this to time spent in the cold English climate.62 Mrs Bentley’s account of those days, however, makes clear that malpractice on the part of the first specialist doctor he visited, who had little interest in the health of a black patient, together with her own pressure on him to complete a translation of the Psalms, delayed treatment until his condition had deteriorated beyond the capacity of contemporary medicine to cure.63 An attempt to restore his sight by surgery was unsuccessful. He was taught Braille by Rev. J. S. Bowskill,64 a skill that brought the avid reader a great deal of comfort. We have several of N’lemvo’s reflections on his condition in his own correspondence and at second hand. What is remarkable in these reflection is the balance between his acknowledgement of his own suffering and the consolations that he was able to find within it:

I was indeed sorrowful that I could not read God’s Word any more, but now I have been taught to read books in Braille and I can read any books. I have “Channels of Blessing and Baptist Principles” and other books. It is very amazing. God has taken away the sight from my eyes and has given me in exchange, to see with my fingers.

I am able now to read whether it is night or day, and whether it is dark or light. It is like Heaven where they do not need eyes, because the Lord Jesus is the Light of Heaven. This is a great joy to me.65

Reflections

Mantantu Dundulu N’lemvo lived a life of consequence and of humanity. He was born in a time and a place dominated by European colonialism. His life, and the lives of those around him were scarred by the cruelty and violence of others. Nevertheless, he spent his life in the care of others, the preaching of a faith that had moved him profoundly, and the work of allowing people to understand one another better through the power of the written word. In the sources related to his life and career, we can see someone passing through the stages of life. We find him as a wide-eyed teenage boy excited about travel and jelly, and the possibility of his upcoming marriage, but wary of hippopotamus meat,66 surprising and delighting his companions with his huge knowledge of plants and animals, and his ability to mimic the latter on request.67 We find him again as a dynamic missionary worker, helping lay the foundations for a thriving Christian community in Congo, literally building the infrastructure of that community with his own hands, and doing everything from running its finances to founding its drum and fife band (he himself played the cornet).68 We find him again in his closing years, after decades of blindness, bringing calm, dignified consolation to his friends and community. When he died, he did so surrounded by his family and venerated as a father of the church in his country. His was a life lived well, and we are proud to help commemorate it as part of Black History Month at Regent’s.

Categories: Uncategorized

Recent Comments