Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition

Posted Thursday, 10th July 2014

Works of Augustine, (Basle: Froben, 1569) 1/2/1000

Most people have an image of the Spanish Inquisition in their minds as the bloodthirsty massacre of 16th century Spanish Protestants in retaliation for the blasphemies of Luther. Although not a pleasant exercise of authority, the Spanish Inquisition was rather less murderous and more bureaucratic than tends to be imagined. In many ways it acted as a civil service not just to the Roman Catholic Church, but also to the monarchies in multi-kingdomed Spain.

The Inquisition was founded in 1478: five years before Luther’s birth, and several decades before he pinned anything to anyone’s door. It was largely set up to monitor Jews and Muslims who had converted to Christianity, but were suspected of continuing to practice their ancestral religions in secret[1]. Given that many of these ‘converts’ had renounced their former religions against threats of violence and death, or had even been forcibly baptised, their lack of wholeheartedness is hardly surprising. Up to 5000 individuals were put to death by the Church during the course of the Inquisition. However, given that it was not totally disbanded until 1834, this averages out at about 14 executions each year, which is in no way out of line with executions carried out in other European countries at this time. Additionally, although heresy trials were the most important work of the Inquisition, many other far more minor legal cases relating to marriage law, blasphemy and general moral infractions. Much the same happened at the Court of Arches in Protestant England.

One function which the Inquisition carried out with great enthusiasm was censorship. The invention of the printing press in distant Germany in the 1450s caused something of an information explosion, and heretical or generally suspect texts could now reach large audiences relatively quickly. The Inquisition – in common with most civil and ecclesiastical authorities – drew up lists of undesirable books known as the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Forbidden Books), which was broadly in line with the first Pope-approved version of 1559[2]. Initially, books on the list were banned entirely, but this soon proved unworkable, and the subtler suppression of pen and ink was applied to many banned books.

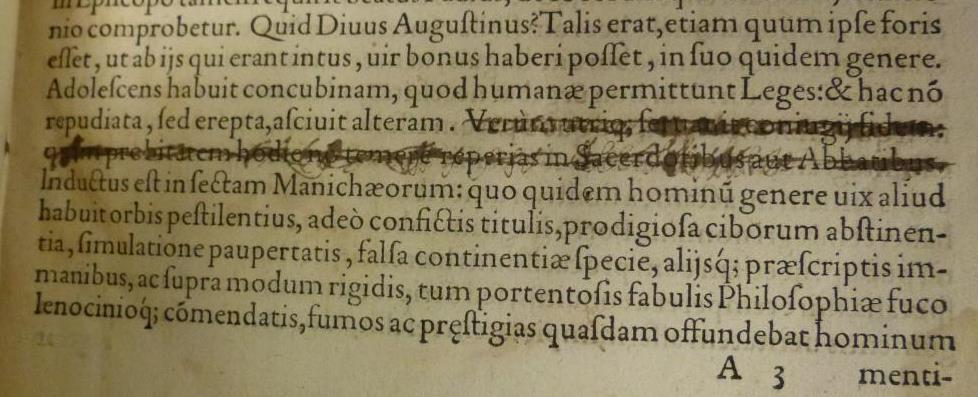

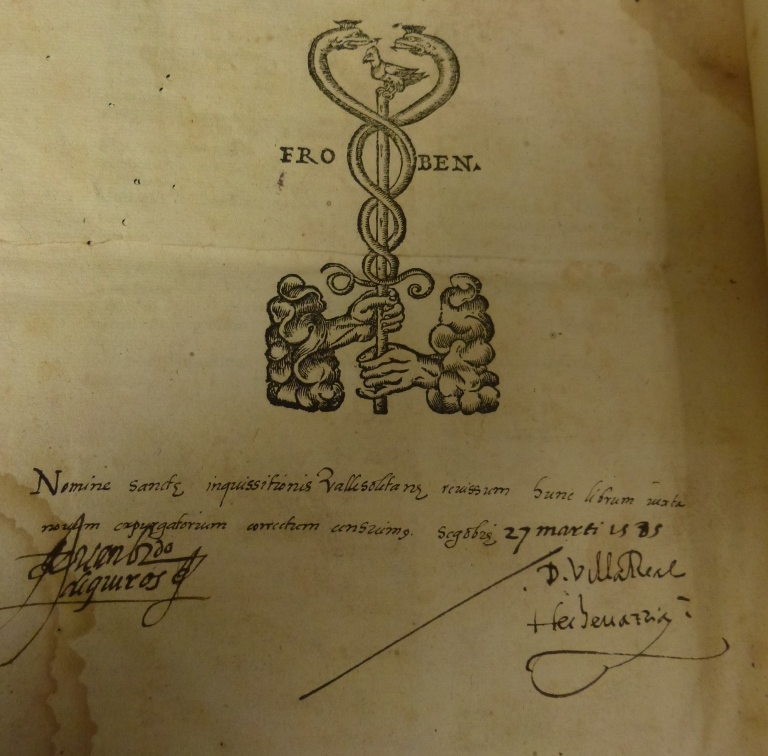

A good example of this has been found in the Angus Library: Primus [-decimus] tomus eximii patris, inter summa latinae ecclesiæ ornamenta ac lumina principis, D. Aurelii Augustini Hipponensis episcopi [The Works of Augustine] (Basle: Froben, 1569). The works of Augustine were, of course, highly thought of by the Roman Catholic Church, but this edition printed in Protestant Basel had some unfortunately Calvinistic footnotes, and left in a few Augustinian sentences about the moral probity of clergy which the Inquisition would have preferred to have been omitted. So a censor crossed them out. To ensure that the censorship was genuine, each copy of a censored work – and each volume of each copy – were signed and dated by the by the authorities on the final page.

The writings of an Algerian author, printed in Switzerland, bound in Germany, and censored in Spain, are now shelved in England. This is less unusual than might be expected. Books forbidden to Catholic Europe not infrequently ended up in Protestant England: Thomas James even used the Index Librorum Prohibitorum as a shopping list[3] for good books to fill the shelves of the Bodleian Library, and plenty of English gentlemen liked to buy impressive books as souvenirs of their Grand Tour. This book’s route to the Angus Library is not entirely clear, but it is safe to say that no-one had been expecting the Spanish Inquisition in a Baptist library.

[1] Henry KamenThe Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. (London, 1998)

[2] The final Papal Index was only withdrawn in the 20th century at Vatican II

[3] P.108 Fred Lerner Story of Libraries: From the Invention of Writing to the Computer Age (New York, 1998)

Recent Comments