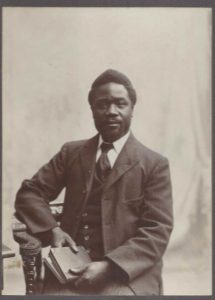

Mantantu Dundulu, N’lemvo. Linguist, pioneer, man of faith.

Posted Friday, 9th October 2020

To celebrate Black History Month, Dr Daniel Gerrard , Lecturer in Medieval History here at Regent’s, is jumping ahead a few centuries from the Middle Ages to write about an amazing man, Mantantu Dundulu, better known as N’lemvo. A superb linguist, interpretor ,translator and possibly the first Christian Protestant convert in Congo, here he commemorates his remarkable life.

In Ngombe-Lutete (Congo) stands a memorial plaque and bust to one of the outstanding figures of early twentieth century African Christianity and linguistics, Mantantu Dundulu N’lemvo. The memorial depicts a dignified, elderly gentleman, his blind eyes hidden behind dark glasses, recalling him as Premier Chrétien Protestant and Batisseur de l’Eglise du Christ au Congo. In a period where much controversy surrounds who and what is commemorated in statue form, we are glad to have the focus in Black History Month on a remarkable man whose contribution was not outweighed by inhumanity but was instead elevated by his commitment to the care and enlightenment of others.

Early Childhood

N’lemvo was born near San Salvador in what was then the Kingdom of Kongo, a vassal state of Portugal, around 1870.1 Many of the details of his early life are disputed or uncertain in our sources, including his unusual collection of names. ‘Dundulu’ means ‘stupid’, a moniker that those who knew him believed he had acquired, either through refusing to admit that he could ‘see’ the spirits of his ancestors at an initiation ceremony, or because he was apparently uninterested in embracing the tenets of Catholicism.2 The ‘Mantatu’ name has a darker story behind it, though an equally uncertain one. N’lemvo himself wrote that he was separated from his father when his father and uncle quarrelled over money, leading to a division of the family’s children.3 A somewhat more lurid story, but one attributed to N’Lemvo, that appeared in Quest after his death, reported that N’lemvo’s father died on the day of his birth, and that his father’ brother and sister were both suspected of witchcraft and killed.4 What is not in dispute is that his early life was marked by tragedy, and that his mother gave him the name ‘Matantu’ (‘Ntantu’ means ‘sorrow’) and he was brought up in the care of his uncle, Tulante Mbidi. N’lemvo left a vivid account of a challenging childhood with his uncle, taking responsibility for the care of siblings, catching eels with his uncle, and trading chickens for strings of beads. He even sought work as a labourer at the age of nine, but was regarded as too young to be effective in that role.5

On 29th April 1881, he was brought by a Catholic priest6 to meet the British missionary and linguist, Dr Holman Bentley, who immediately became both his teacher and his employer.7 It was Bentley who gave him the name N’lemvo, for his birthplace of Lemvo, which also means ‘obedience’, a name that apparently suited the gentle personality of the boy very well.8

Education

N’lemvo’s meeting with Bentley was a decisive event in the life of both men. In time, N’lemvo would become enormously important to Bentley’s linguistic work as well as his evangelism, but there were stumbling blocks along the way. N’lemvo was initially worried that at least some of Bentley’s acquaintances might be cannibals! He was afraid on his first encounters with the written word, though quickly mastered the alphabet, the basics of English pronunciation, and was able to begin moving on to a more advanced level of education.9 He also quickly began to express interest in converting to Christianity, telling Bentley of his ‘personal trust in Christ’ by 1882.10

Travel

The Bentleys brought N’lemvo to Britain three times. His first visit had him arrive on 23rd March 1884.11 His second visit, had him arrive in April 1892.12 His third visit extended from 1904-1907.13 Though Dr Bentley viewed these visits as primarily an opportunity to focus on his linguistic work, and in particular of seeing publications through to press, these visits, which went via Normandy and Holland at least once, were also important educational opportunities for N’lemvo. He was taken to see the medieval remains at Caen,14 addressed the Pekela church congregation at Rotterdam (with translation helped by Mrs Bentley),15 and showed interest in a huge range of north-western European cultural idiosyncrasies, from glass blowing and peat cutting, to the practice of men engaging in agriculture.16 He was present at the Bentleys’ wedding, and wrote home of the strange custom of European ladies marrying while wearing mosquito curtains (i.e. wedding veils) over their heads!17 His own recollections of his first visit in particular are full of energetic enthusiasm for a trip to a coal mine and to Windsor Castle. Though disappointed that he did not have the opportunity to meet Queen Victoria in person, an enterprising member of the castle staff gave him a plate of Jelly and told him that he was eating the queen’s leftovers, which he happily and excitedly reported back.18

Linguistic Work

It is clear that the young N’lemvo was a precocious linguist. Though he had only begun to learn to read in 1881, by 1884 he was already at work with Bentley on what became the Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language.19 Bentley acknowledged the importance of precise local linguistic knowledge in both aspects of his own work:

A superficial knowledge of a language may suffice the trader, or explorer; but a very deep and thorough acquaintance should be sought by those who seek to inculcate religious truth, and to translate the Word of God.20

We might express a reservation that Bentley did not directly acknowledge N’lemvo’s support in his preface, but the frontispiece of the volume does have a photograph of Bentley, his wife (also much involved in translation work), and a young man who can only have been N’lemvo. Indeed, Bentley’s wife was keen in her own recollections to emphasise the importance of N’lemvo’s contribution:

While we were home on furlough in 1898 my husband succeeded in passing through the press, the Congo Grammar, Appendix of the Dictionary, and Congo Testament, every word of which had been subjected to Nlemvo’s keen criticism, who had been his helper in the language from the very first, and knew English well enough through having been to England three times and studied the language very carefully.21

In 1893, N’lemvo published his own translation of the book of children’s religious instruction, The Peep of Day.22 After their second trip to England, in 1893, Bentley and N’lemvo completed work on the translation into Kongo of the New Testament.23 These are the works for which he is most famous, but it is clear that he made contributions to a much wider array of work than is generally recognised. He supported Mrs Bentley’s work on a Harmony of the Four Gospels,24 and her assembly of a vocabulary of four languages (Congo, French, Portuguese and English),25 and her ‘History of the Israelites’.26 Even in old age, having lost his eyesight many years prior, he was still working with Rev. W.B. Frame on a new translation of the New Testament , and with R.L. Jennings on a translation of Stalker’s Life of St Paul.27

Christian Life and Evangelism

N’lemvo may have taken communion as early as January 1885, in England but he returned home to Congo for his baptism at Wathen on February 19th 1888.28 In 1889, he became one of the founders of the Wathen church.29 He was immediately made Deacon and Treasurer, and became superintendent of evangelical work.30 He himself built the first brick chapel at Nionga.31 His local connections into clan leadership helped his own evangelism to gain a popular hearing, and he was soon gathering small crowds at the nearby town of Vunda on Sundays.32 In July 1905, he was asked to speak on behalf of the Congo churches at the Baptist Congress at Exeter Hall. By that point, he was able to speak not only of his own joy in his conversion, but also of the conversion of nine or ten thousand of his countrymen.33 Contemporaries were clear that the dramatic successes of conversion in these years owed a

great deal to his ‘persistent enthusiasm’34. By his death in 1938, the number of converts may have grown to as many as two hundred thousand.35

Caring Roles and Supporting the Community

Though his linguistic and evangelical work constitute the core of N’lemvo’s historical legacy, it is clear that he made an incredibly broad range of contributions to his community in life. Often we find traces of him in caring or nursing roles, as when he supported Bentley during the latter’s period of failed eyesight,36 when he distributed vaccines at Vunda during a Samallpox outbreak,37 or when he rushed back to be at the bedside of his dying mother.38 We find him assisting in an operation to remove a girl’s eye,39 nursing a Medal Chief,40 building roads to help speed local traffic,41 hunting to bring his community food during a meat shortage,42 and dramatically saving at least two lives, one of a young man accused of witchcraft43 and another during a leopard attack.44

N’lemvo’s position as a convert did not make his relationships with his own countrymen easy. Though he inherited a chieftainship from his uncle, his Christianity was not compatible with the role, which he surrendered to another uncle.45 Proving that his religious affiliation had not broken his bonds with the community took time and effort. The lavish funeral that he conducted for his mother seems to have helped convince many that he was respectable,46 and over time we find growing evidence of his status as a community leader, especially in the resolution of local disputes.47

Personal Life and Relationships

N’lemvo’s correspondence, and the recollections of those that knew him, emphasise strongly his friendships and his wide range of personal interests. When they first met, Dr Bentley was not always certain how best to develop that relationship, whether as N’lemvo’s employer or in loco parentis,48 and it is clear that his upbringing of N’lemvo involved some corporal punishment, as was usual in parenting in the period.49 Nevertheless, his close friendship with the Bentleys is attested in many places. He felt the loss of Dr Bentley very keenly,50 and wrote with joy at the erection of a memorial plaque at Kibentele to his old friend’s life and work.51 In his correspondence with Mrs Bentley, the deep affection between the two can hardly be missed. Even in his old age, he described himself as her ‘child’.52

We know less about his family relationships, though these were clearly deeply important to him. He married twice, the first time to Kalombo in 1888.53 Kalombo had been captured by Arab raiders and forced into slavery, but was rescued and brought to the Mission station, where she and N’lemvo met.54 Kalombo died on 13th November 1898 after a long illness, and N’lemvo married again three years later (though our sources are silent as to the identity of his second wife, beyond that she came from the Katanga region.55 Although N’lemvo’s life was yet again marked by tragedy, when his eldest son, Kikudi was killed choking on a fishbone in 1893,56 he took great joy in his growing family. By the time of his death he had at least eleven grandchildren.57

N’Lemvo’s particular interest in and care of children is a theme that runs through our sources for his life,58 beginning in his own childhood, when he was responsible for caring for his sisters. He vowed that his own children would never be separated as he had been from some of his siblings,59 and it is striking that in his correspondence with Mrs Bentley he shows particular interest in how the legacy of her translation work was contributing to children’s education in French several decades later.60 It is characteristic of this interest and care that after he lost his sight, N’lemvo took the opportunity of a young British girl reading the New Testament to him to gently begin her own education in scripture.61

Blindness

N’Lemvo spent the last three decades of his life blind. Since he began to encounter serious difficulties with his vision on one of his trips to England, a number of contemporaries attributed this to time spent in the cold English climate.62 Mrs Bentley’s account of those days, however, makes clear that malpractice on the part of the first specialist doctor he visited, who had little interest in the health of a black patient, together with her own pressure on him to complete a translation of the Psalms, delayed treatment until his condition had deteriorated beyond the capacity of contemporary medicine to cure.63 An attempt to restore his sight by surgery was unsuccessful. He was taught Braille by Rev. J. S. Bowskill,64 a skill that brought the avid reader a great deal of comfort. We have several of N’lemvo’s reflections on his condition in his own correspondence and at second hand. What is remarkable in these reflection is the balance between his acknowledgement of his own suffering and the consolations that he was able to find within it:

I was indeed sorrowful that I could not read God’s Word any more, but now I have been taught to read books in Braille and I can read any books. I have “Channels of Blessing and Baptist Principles” and other books. It is very amazing. God has taken away the sight from my eyes and has given me in exchange, to see with my fingers.

I am able now to read whether it is night or day, and whether it is dark or light. It is like Heaven where they do not need eyes, because the Lord Jesus is the Light of Heaven. This is a great joy to me.65

Reflections

Mantantu Dundulu N’lemvo lived a life of consequence and of humanity. He was born in a time and a place dominated by European colonialism. His life, and the lives of those around him were scarred by the cruelty and violence of others. Nevertheless, he spent his life in the care of others, the preaching of a faith that had moved him profoundly, and the work of allowing people to understand one another better through the power of the written word. In the sources related to his life and career, we can see someone passing through the stages of life. We find him as a wide-eyed teenage boy excited about travel and jelly, and the possibility of his upcoming marriage, but wary of hippopotamus meat,66 surprising and delighting his companions with his huge knowledge of plants and animals, and his ability to mimic the latter on request.67 We find him again as a dynamic missionary worker, helping lay the foundations for a thriving Christian community in Congo, literally building the infrastructure of that community with his own hands, and doing everything from running its finances to founding its drum and fife band (he himself played the cornet).68 We find him again in his closing years, after decades of blindness, bringing calm, dignified consolation to his friends and community. When he died, he did so surrounded by his family and venerated as a father of the church in his country. His was a life lived well, and we are proud to help commemorate it as part of Black History Month at Regent’s.

Categories: Uncategorized‘Just a Novelty’ …. Taking a Bioscope to the Congo

Posted Wednesday, 29th April 2020

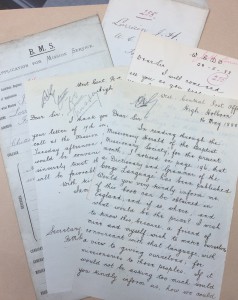

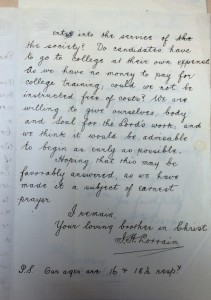

Looking through some files in this strange time of working at home, I came across copies of letters written by a young man named Frank Oldrieve in the summer of 1905 . Frank was about to become a missionary in what was then known as the Congo Free State (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and he was writing to Alfred Baynes the secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society asking for permission to take a Bioscope with him, a very early travelling film camera , so that he could visit various mission stations and take ‘Cinematographic pictures of the people and work’. Frank must have had a good idea of where the future lay in terms of the appeal of film, even though he refers to it at the time as ‘just a novelty’.

At the time that Frank went out to the mission station at Wathen, Ngombe Lutete, the people of the Congo were still enduring the brutal regime of the Belgian King Leopold II, under which many millions died of disease, exploitation and violence. Frank would have witnessed terrible scenes and indeed many Baptist missionaries stationed there at the time such as ,Rev A.E. Scrivener and John Weeks wrote harrowing accounts and took photographs to highlight the cruelty of the regime and contribute to the campaign to end it.

Here, Frank is a young man of 25, living in Clapham, anticipating his journey to Africa and trying to persuade Mr Baynes of the power of the movies!

Note that the sum of £47 in 1905 is the equivalent to roughly £5, 500 today.

People who are not interested will come and hear about Missions when there are “Animated Pictures” when otherwise nothing else would induce them to do so. This has been proved over & over again. It is also a financial success to have Cinematographic Exhibitions and I only mention one case which came under my notice quite recently where the B.M.S took £47 from the “Living Picture Section” at a Missionary Exhibition held in Lancashire.

As far as I can find out no Bioscope has ever before been taken to the Congo & I count it no small honour to be asked to take the first pictures ..the machine which cost about £50 is lent free of charge & all the Society have to pay for is the film , the cost of which would very soon be covered

Mr Baynes obviously granted permission and in the next letter from Frank ,dated August the 25th 1905, he writes:

I have this morning consulted the 2 leading Photographic dealers here -both of whom are expert Bioscope operators -& they have given me a good deal of advice as to the make of Machine & how to work it … I think we shall be able to get an Instrument, case, stand, lens etc for about £40.The films will of course be extra. When I arrive in London I will consult a well-known firm of Bioscope Makers & I will take lessons from them as to the working of the Machine….I shall also, of course, be glad to have fuller instructions as to where you wish me to go, what sort of pictures you would like to have, & whether you would like me to go off at once & visit the other stations.

Frank stayed in Wathen until 1909 when he left to take charge of a station under the Mission to Lepers in Northern India. He worked hard to raise awareness of the problems of controlling Leprosy and eventually helped to found the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association, of which he became the first General Secretary. He travelled widely in the interests of the association, until he relinquished the post due to failing health. He later became secretary to the South African Auxiliary of the Mission to Lepers and died when he was still working on the 21st March, 1948 at Mbabane settlement.

BMS missionaries George Grenfell and Rev Lawson Forfeitt with bioscope, the Congo ,1900s

Categories: UncategorizedAn Elephant Ride to Chitor

Posted Friday, 22nd November 2019

Hello, from us all at the Angus. We’re back again after quite a while , but we are as busy as ever!

Today on this cold and grey November morning in Oxford I thought it might be good to have a glimpse into the daily journal of Clara R Southwell . A member of the committee of the Baptist Zenana Mission, Clara toured India from late 1907 to early 1908 writing vivid accounts of her experiences whilst visiting Zenana stations across the country. The Baptist Zenana Mission was established in 1867 with the aim of converting Indian women to Christianity . Female missionaries could visit the private area of houses , the Zenana, where only women were allowed to go.. By the time Clara wrote her journal ,the BZM was involved with education and medicine, setting up many schools and hospitals, some of which still exist today. In this extract written in mid November 1907, Clara is off to Chitor , also known as Chittor or Chittaugarh, now a major city and municipality in Rajasthan and she wasn’t so keen on her means of transport….

I cannot say I enjoyed my elephant ride. The animal kneels down and one climbs up by a ladder on to a flat padded seat on his back, which has an iron railing all round to keep one from from falling off. We had to sit back to back,with our legs dangling over the elephants sides. It is a horrible sensation when he gets up and one is jolted first one side and then the other. I was thoroughly uncomfortable and more than half frightened all the way; and when the beast went down a steep bank and up the other side , and forded the river, it was decidedly terrifying. One could feel that he was very sure footed by the careful way he put down each foot, and he went at a slow steady pace throughout. We had to go about 3/4 of a mile across a bit of jungly plain-the dark mass of the ancient city facing us. Chitor stands on a mass of rock rising out of the plain at an angle of 45 degrees, and 3 1/2 miles long across the top-the width of the rock at the top is only 1200 ft. It is surrounded by a high massive stone wall, with curious battlements, pierced for firing from , and with fine bastions. The road is not very steep but much zigzagged, and one is mounting all the while….then one passes under 7 fine stone gateways before reaching the fairly level gateway at the top, on which the city stands, or rather stood. For it is a mass of ruins…We were there at sunset and the light was wonderful . We went into Padmans (sic) palace (13th century) all blue and white , with a smaller palace on an island in the middle of the lake….

Chitor is now quite deserted and wild animals live in the jungles on the slope of the hill. It is a weird and fascinating place with its reminders of ancient chivalry and cruelty As soon as the sun set we started out on the return journey. Fortunately for us it was bright moonlight, or it would not have been pleasant crossing the jungle. Instead of fording the river we crossed it by the fine old 14th century bridge, and altogether had not so much jolting as before. However, we were all thankful to reach the Dak Bungalow near the Railway Station, and get on to terra firma again-the next day my arms and shoulders were quite stiff from holding on so tight to the iron bar, for fear of being pitched off the elephant’s back.

Categories: UncategorizedEscaping to 1896 India…

Posted Wednesday, 7th October 2015

It’s been a very busy few days here at Regent’s Park College. All our new students have arrived and there is a much busier, more vibrant feel to the building than there has been over the summer. All of the academics are here. The main office is hectic. As for the Library – Emma, our college Librarian, has been busy doing inductions, Sukie has been busy with exhibitions, Lucy with the cataloguing, Julian with his Adlib database, Celia and Emily have been very busy with visitors and requests for information, and I have been busy setting up an online shop on Abe Books. We have some real treasures for sale. Some are duplicates, some do not relate at all to Baptist history/theology, but all of them are old and/or rare. Please do have a look at our Abebooks shop, (http://www.abebooks.co.uk/the-angus-library-and-archive-oxford/60538303/sf) and our Amazon one for that matter (www.amazon.co.uk/shops/RPC) , as we are in need of funds. Thank you!

So, it is the end of the working day on Wednesday (7th October 2015) and I thought a few minutes with Mr Lorrain & co. would be a suitable way to wind down. So sit back, have a cup of tea and relax as we find out what J Herbert and Fred were up to in 1896 India…

“There has not yet been sufficient rain to make the river rise high enough to allow the large Calcutta steamers to come up so far as Silchar, so we have to be content with the smaller boat. We spend the whole day on the steamer, puffing away down stream, twisting and turning with the tortuous course of the river. Now the beautiful North Cachar hills tower up before us, now we seem to be leaving them behind us, now they are on this side, now on that. The man at the wheel has as much as he can do to turn us round the sharp bends & is incessantly spinning the wheel round, first this side, then that. We are sitting on the upper deck on the part marked off for Sahibs & we wonder what the poor natives must be suffering if this is what they call first class accommodation. The propeller takes good care that we so not forget that it is doing all the work, for it keeps the deck in a constant state of vibration; we can scarcely sit in our chairs, our heads bid fair to jump off our bodies. A poor old gentleman close by, who is a regular Tichborne, seems to be suffering agony. We attempt to read but it is an impossibility & the noise of the engine makes conversation anything but pleasant. So at last we resign ourselves to our fate, hanging on to our chairs & hoping that we shall not fall to pieces before we reach the end of this first stage in our journey. At Budarpur we see the piers of the bridge which is being built across the river & we can also see the cutting on the low hills not far away & we wonder how many more years will pass before the long promised railway to this place is really opened. The fat gentleman gets off here & we go on, and sometime after dark reach Fenchoogang where we anchor for the night.

During the dry season & the early rains it is the custom for passengers from Silchar to Calcutta to change from the small steamer to the large one at Fenchoogang. But we are not going direct to Calcutta. We have planned to strike northwards from this place and to get to Calcutta by a very circuitous route, passing through the whole length of the Assam valley on our way thither. As previously arranged by telegraph we find two pony traps awaiting us on the other side of the river when we awake in the morning. We accordingly hire a boat, put all our belongings aboard & direct the Indian in charge to land us on the opposite shore. Nothing more forlorn & piteous can be imagined than the two wretched beasts which are brought out & put into the shafts of the two ramshackle conveyances, which for courtesy’s sake we call “pony carts”. It seems almost a sin to give these poor creatures the trouble of dragging us & our luggage all the way to Sylhet, and it is with a feeling of guilt that we climb into our seats, Fred and K in one trap & Khuma & I in the other. The luggage is stowed away in a net under the carts & requires a good deal of watching to prevent it from jumping out. There is a driver to each conveyance & they commence the journey be belabouring their wretched steeds with thick sticks, choosing as it seems to us, the most skinny parts on which to strike. I now turn my attention towards the creature which is slowly drawing my trap along, & I marvel that men can be so cruel & heartless as to keep such wretched animals in constant work. The one upon which I am gazing seems to possess absolutely no flesh, & is a mere framework of what once presumably was a pony; the bones stick out to such an extent that with every movement they look as if they must burst through the skin, & where the larger bones project beyond their surrounding prominences they are one mass of open sores caused by the rubbing of the rude harness & of cuts & bruises made with the driver’s stick. I remonstrate with the native in question, & for a time he puts aside the stick, but the animal has grown so used to being thrashed that he positively refuses to be persuaded by any other means. I look round & see that Fred’s pony is even worse than mine & besides having a wretched personal appearance has a vile temper, & every now & then stops short & threatens to back them into the ditch. It is with some amount of fear for my friend’s safety that I watch the antics of the little brute, but by & by the fit passes and we all jog on again & come to the first ferry. There is a good deal of delay here, but eventually we are trotting along as gaily as ever. The country through which we are passing is perfectly flat, the road is raised slightly above the level of the surrounding rice fields, which at the present time are just beginning to be covered with water. On either side of the road is a wide ditch from which the earth has been cast up to raise the road above the water. Here & there we pass a native turning over his patch of soft muddy land with a primitive looking plough drawn by a yoke of oxen, or wending his way homeward with his oxen before him and his wooden plough on his shoulder. We are not getting on at all well, there are numerous stoppages, first one & then the other of the horses takes it into his head to stop or go backwards or sideways & so we are not at all sorry when we spy a man coming towards us on horse-back at full gallop, whom we are given to understand is something to do with the proprietor of our turnouts. Upon reaching us he salaams respectfully & goes off to rescue Fred & K. who are just on the point of being precipitated into the ditch backwards. The man on horseback puts his steed in front of the one in the cart, & then starts at a gentle pace, the other following like a lamb. When he comes up to me he gets in front of my horse & puts on some speed & away we all go after him. This is something like, and we are speedily at the last ferry. On the other side we find a kind of antiquated close cab awaiting us, it evidently being though below the dignity of a sahib to drive into the station of Sylhet in such swell conveyances as those we have just vacated. The luggage is piled on the roof of the cab & one of the little carts is also loaded & away we go!”

Categories: UncategorizedHidden treasures, part 5. In which I realise that this diary is written by Herbert J Lorrain and was sent to his mother as a gift

Posted Friday, 25th September 2015

First of all, today’s excerpt for your enjoyment:

“On Monday morning we are up betimes, soon after sunrise we pass by the piles of the new bridge which is to bring the train across the river & so on to Silchar. There are numbers of cooleys at work, but very soon the rains will swell the river & the whole will be under water until next autumn. It may easily be understood that work of this kind is slow & that years perhaps will elapse ere the steam engine is seen bearing its freight of passengers & goods into Silchar. By six o’clock we have reach the mouth of the river which has borne us upon its bosom from the heart of the Lushai Hills & now we turn our heads upstream on the wider river Barak. The boatmen no longer sit at ease & merely guide the crafts, but are on the shore tugging at the towing lines. K’s deserted boat & our own are lashed together & one man guides the two while the remaining 2 men tow us along. The cook boat is not far behind & we can see our boy Khuma sitting outside & trying to take in the big river at a glance, & surveying with wonder the vast expanse of flat country on either side. A crowd of ugly vultures, 26 in number, quarrelling over the carcass of a cow as it floats down with the stream, is of great interest to him, for these repulsive looking creatures are unknown in his native hills. Just before breakfast time we spy a number of men pulling a drag net to shore, so we go across the river to them & watch them as they labour at the heavy ropes. A large area of the river has been enclosed by a net some quarter of a mile in length, & now, men are standing at either end slowly & laboriously & with many a shout & grunt pulling the net ashore, every minute lessening the area enclosed & consequently crowding the fish closer & closer together. We watch for a quarter of an hour & by that time the men at wither end of the net who were originally standing about 100 yards apart have gradually moved along the shore & now are close together, the net is almost all drawn in, when two or three men jump in the water to keep the fish from escaping when it is finally drawn ashore; the whole surface of the water inside the net is one mass of struggling fish & one huge monster nearly succeeds in bounding over the net, but is quickly knocked back again by the alert fishermen. At last the word is given & with infinite care & rapidity the whole finny company is hoisted on to the beach, kicking & jumping in the bright sunlight to the infinite delight of our Lushai lad. We leave the servants to wrangle with the fisherman & take a short walk getting on the boat when we hear that the fish are fried & ready. So passes the day, quietly and uneventfully, until at last the puffing of the Silchar steamer is heard behind us & our boy is all alive to see the wonderful “Fire Boat” of which he has heard so much. His dreams however seem to have exceeded the reality, for when the great ugly, soot-begrimed stern-wheeler goes grunting by upstream he remarks how very slowly it travels & seems to be somewhat disappointed. But the lumbering old boat pays us out for our disrespect by giving us a good shake up after she has passed & nearly driving us upon a rock. Next day at noon, Silchar comes in sight, with its long row of “go downs” and imposing crowd of country boats, steamers & barges. Slowly we pass them by on our way to the landing, which at last we reach, &climb the rude steps cut in the steep bank & stand once more in a place which can boast of a certain amount of civilization & which we in the wilds of Lushai-land amuse ourselves by dubbing “The Metropolis”. K’s servant is on the bank to meet us & informs us that K. is rounds at the “Hotel”. (please note this word). We accordingly make for that imposing edifice (which by the way is nothing more than a thatched bungalow), & greet our friend once more. We next go in search of our old friend & fellow missionary Dr. J. & find him in a new house close by, with his wife & little son. We have arrived somewhat before the expected time, as we had wired from Jaluacherra that we should put in an appearance on the following day, but we did not think then that we should have made any progress on Sunday. However, a day earlier or later in India is of no consequence & we are soon made perfectly comfortable in a nice large bedroom, where everything speaks of the presence in the house of a lady. What a delightful rest it seems after the hot journey & how nice, when our boxes have arrived from the boat, to change our clothes & make ourselves look something like civilized beings. K. says that business matters will detain him here until next Monday, so we have several days to spend with our friend Dr. J. and his wife, & they are days of real pleasure. The bachelor life we live in our mountain home makes this happy home seem truly a little paradise, & our kind hostess does everything she can to make us feel that at any rate we can always reckon on having one Indian home, in whose charmed circle we shall be always welcome. The newly arrived son & heir is just able to sit up & make himself interesting & many an hour we spend fanning the poor little creature, who however seems to bear the extreme heat very well, which is more than we do. The change from the comparatively cool climate of Aijal to the tropical heat of Silchar is about as much as we can bear, but in a few days we find ourselves getting used to it, however we still wonder how we could have lived a whole year in Silchar, as we did before going to Lushai, and not know that it was such a warm place. Dr. J. is busy building a temporary house away on the other side of the station & is over there the greater part of the day looking after the native workmen. Occasionally we accompany him thither & watch the men as they slowly fasten up the reed walls, or the women as they smear over the said walls with a mixture of cow dung & mud, or the gang of prisoners from the neighbouring gaol as they creep like so many snails from the tank which is being excavated over yonder to the house, with baskets of earth upon their heads which they empty in the verandah to raise the ground above the surrounding flat. Each man has a wooden ticket suspended round his neck & some are in chains, & there is little fear that they will over exert themselves. Dr. J. tells us that just before we came down, they had a great storm. The house then was nearly thatched, but there were no walls up, & the wind blew the whole down & gave our friend no end of trouble. On Wednesday evening there is a Bengali service in the little girls’ school & among the native Christians we recognise many familiar faces, & receive from their owners many profound salaams. Fred gives a short address in English as there are some present who know, or think that they know, that language and I follow by one in Bengali, in which I find it very difficult to keep myself from using Lushai words now and then. Our English concertinas are much appreciated & help in the singing greatly. None of the missionaries here seem to have a taste for playing and if they have, they certainly do not exercise it in the services. There are two unmarried ladies here working in the zenanas & of course we are invited over to tea one afternoon, together with Dr. J. and his wife. There are some very nice little native children about the house, orphans who have been taken under the protecting wing of these 2 zenana workers. At tea they stand round the room with fans, and work their little arms amazingly in their efforts to make us cool. What comical creatures they must think we Sahibs are, to drink hot tea when the temperatures in up in the nineties & then to want the punkahs to make us cool again. But to change the subject to something not quite so warm. We take our little Lushai boy round to the “godown” – a kind of barn in which all kinds of European stores are for sale & what in America would be called a “store”. The proprietor is an Englishman & his wife comes from that charming island in the Thames not 100 miles from London & known as the ‘Isle of Dogs’. We inspect the store & by & by are shown the new ice machine which has lately been set up at no small expense. Knowing that our boy has never seen such a thing before, we get a piece of ice from the storing vats & hand it to him, and it is highly amusing to see how quickly he drops it & looks to see if his finger is burnt. He can scarcely believe that it is not hot & it is some time before he can make out whether it is hot or cold. But at last the times comes to bid our friends farewell, & early on Monday morning we are on board the steamer with K. and his dog.”

As you can see from the excerpt above, there is reference to a ‘bachelor life’ at Lushai, which I have to admit completely confused me. I thought this diary had been written by a Mrs Lorrain. Until I started doing some reading about James Herbert Lorrain and looked at other items in the archive.

I started with his BMS candidate papers. The candidate papers we hold here at the archive can sometimes have many letters enclosed in the file, and some of them have very little at all. Unfortunately James Herbert Lorrain’s papers fall into the latter group.

As can be seen in the photographs above, James Herbert Lorrain was rather young when he applied to become a missionary – 18 and a half – and his friend was only 16. When they applied to become missionaries in May 1888, they were both working at the West Central Post Office in High Holborn (and could not afford to put themselves through college). Then I compared the beautifully-clear handwriting of the journal and letters, which were certainly written by the same person. Finally, I found out that James Herbert Lorrain did not get married until 1904 to Eleanor Mabel Attkinson. So, yes, I’ll be going back and editing the first couple of my blog posts about this diary!

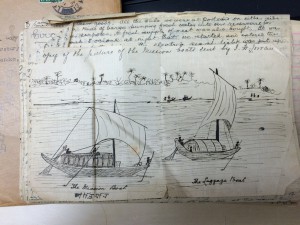

I end with a rather wonderful sketch, which was most certainly done by James Herbert.

Categories: Uncategorized

Our Top 5 Tips for Creating Exhibitions on a Budget.

Posted Monday, 21st September 2015

Over the last 3 years the Angus has produced four pop-up exhibitions as part of our current Hidden Treasures project which is being funded by the HLF and BUGB. This funding has allowed us to work with a very modest budget. We’re not complaining, working with even a small budget is a hundred times better than our previous outreach budget of Absolutely Nothing.

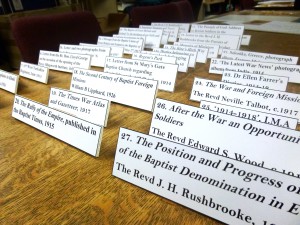

As the final exhibition in this series is on display this week, we thought we would share our top 5 tips for putting together an exhibition on a budget:

1. Find hidden talents

You will be surprised at the range of skills you can find in a small team, so make the most of what you’ve got. Recently one of our volunteers created a set of wooden audio listening stations from reclaimed wood. It turns out we also have a professional voice actor on staff who has contributed great recordings to install in the listening stations (thanks Will!).

2. Flexibility is key

If you are investing in professional equipment such as display stands and cases, try to invest in a system that is as flexible as possible so that it can be used again next time.

3. Professional printing doesn’t always cost the earth

These days professional printing doesn’t have to blow your whole budget in fell swoop. Posters, pamphlets and booklets can be designed on software such as Publisher, Photoshop or Gimp (which is free) that can be sent away for immediate printing. If you get confused by terminology such as bleeds, crop marks, CMYK and RGB, we’ve found that most commercial printers are happy to offer advice on making documents print ready. To keep costs down, stick to standard paper sizes (A4 or A5) and get quotes for different paper weights.

4. But see what you can achieve in house

If you are handy with spray mount, a craft knife and hot glue gun you can get a long way on your own. Just because the process it simple, it doesn’t mean it can’t look professional. While we send some things out for commercial printing, we produce our display panels and labels in house using stiff foam mounting board and I think they look pretty slick.

5. Thank your volunteers!

The Angus relies on the hard work of our Exhibitions Volunteer team, who carry out the majority of the research and interpretation work. Our volunteers get the opportunity to contribute ideas and work that has a direct effect on how the final exhibition looks. We hope that the experience of co-curating an exhibition means that the time they give us in the archive pays off, but we still can’t thank them enough for all the hours they put in to make these exhibitions happen and we hope they’ll join us again next time.

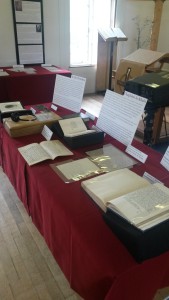

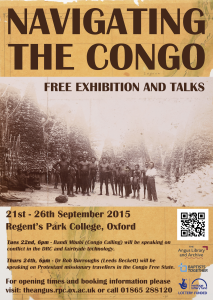

Our new exhibition Navigating the Congo is open 21st – 26th September 2015 and looks at missionary work in the Congo during the 19th and early 20th century. Visit our exhibition page to find out more about the exhibition and talks!

Categories: Events Exhibitions VolunteeringHidden treasures: Part 4 – A very solemn Sabbath

Posted Tuesday, 1st September 2015

Next morning we wake to find it raining, but this does not hinder us in the least; the naked boatmen perhaps work all the harder, for the air is cool & pleasant. At 8 oclock [sic] in the morning we reach Jaluacherra the first sign of civilization we have seen since leaving Sairang, here we find a few rude huts, a miserable shanty bearing the legend “Post & Telegraph Office” upon a board, & a dilapidated looking stockade crowning the hill just behind it. A more wretched looking spot it would be hard to find, surrounded as it is by dense jungle & possessing a climate the reverse to pleasant. We only stop here to see if there are any letters for us & then we are off again. Presently we are gliding along within sight of a tea garden, then another stretch of jungle & another garden & so on the whole day. The beautiful mountains are left far behind & nothing bot low hillocks and flat plains can be seen. At last the day is done, we stop to take our dinners & to give the men time to eat their rice & then we are off again. The rain has cleared off & the sky is full of stars which give sufficient light to enable us to see where we are going. A man sits in front of each boat looking out for snags, while the man behind works the large oar which serves as rudder & propeller. K. is in front sitting outside his boat & we are not far behind enjoying the still beauty of an Indian evening. We play a hymn on our English concertinas & the sound of some familiar tune goes floating on the breeze, perhaps startling the natives as they lie half asleep in their bamboo huts, or attracting the attention of some dusky fishermen as he patiently plies his net, and bringing to our minds & perhaps to the mind of our fellow traveller thoughts of the dear homeland & of those who once joined with us in singing those grand old hymns. Hour after hour goes by & still the men work away, for they have to reach a certain landing before they tie up. Presently we go inside & lie down & the next thing we know is that we have arrived at our desired haven & that it is 11.30p.m. and we say to ourselves that we must have been asleep. When the sun rises on Sunday morning we find ourselves alongside a sandy beach, a few huts surrounded by the usual banana, papaw & jack, trees is all that is visible. We climb the bank and find a fair-sized shed called in this country a “godown”, well stocked with English stores, wines & spirits. The owner is a portly Babu, who no doubt does a fair trade among the Planters in the district. This lively place is known as Kalacherra & from here K. has arranged to wide across to Silchar. The pony is waiting for him close by, & it is not long before he starts off. Being Sunday we intend to spend the day here and give the men a rest, but they do not seem at all inclined to fall in with the proposal as they are so near home. Knowing that there will practically be no work to do, if we allow them to put out into mid-stream and float down with the current, we let them have their way & all day we are gliding gently past pretty native villages & tea gardens. All nature seems so bright and happy, & it is hard to realise that we are already approaching a district where death in one of its most awful forms is working havoc amid these sunny homesteads & wringing many a heart with bitter anguish. Yet it is, alas, only too true, the fearful scourge, cholera, is all at work here. We glide on. The cries of the mourner reach our ears; all thoughts, save that we are in the presence of death, are forgotten. Ahead, on the margin of the water we see a fire burning, we know what those figures flitting to & fro’ in its light are doing. We draw nearer & now we are within a few yards of it, can see the form of the poor unfortunate lying midst the flames, & can hear the fizzing & spitting as the tongues of fire leap about the emaciated body. The water of the river laps around the funeral pyre, & soon all that remains of that once manly form, which but a few hours ago was hale & hearty, will be cast into the stream, will float down & contaminate the water, & who can say where the mischief will end? We hear the boatmen exchange greetings with the group around the fire & hear the dread word “cholera” follow us as we glide out of sight. A little further on we see an object floating upon the water & as we pass it we catch sight of a woman’s form, rising & falling with the ripples, & we wonder whether she has been cast there by her cruel neighbours because she did not happen to be of their particular caste, or whether she had been seized by the fell disease when in the act of drawing water, or bathing & had not strength enough to drag herself to the shore. By this time all the boatmen are talking of nothing else but “cholera”, relating past experiences & raking up all the most fearful stories of its cruel ravages. Presently a man hails one of our boatmen from the bank, & tells him that a certain relative has been carries off & that the family are anxiously awaiting his arrival. Poor fellow, his face looks so sad as he gathers together his few belongings & asks our permission to leave the boat. It is explained to us that two of the boats can be lashed together when we reach the big river on the morrow so that our progress will not be retarded by the absence of one hand. We give our consent & by & by the youth jumps ashore & makes for his home across country. The river is now very dirty, & sometimes covered with scum & debris & as we are hoping that we shall not be obliged to drink any of its polluted water we see the cook dipping up a pot full, & know that at any rate our dinner will be cooked in it. There is no help for it however, no other water is available & like the poor inhabitants who live on the banks we must take our chance, trusting that the cooking process will deprive the microbes of their usual vitality. We drift on long after sundown in order to get beyond the villages & it is late before we tie up for the night. The Sabbath has been a day of solemn thoughts, we have been brought face to face with death & we have tried to impress the boatmen with the fact of their nearness to the other world & of their need of a Saviour like Jesus who alone can rob death of its terrors & secure to us life eternal.

Categories: UncategorizedNavigating the Congo: Free Exhibition and Talks

Posted Friday, 21st August 2015

Booking now open!

21st September – 26th September 2015, Regent’s Park College, Oxford

Featuring artefacts, navigational equipment, maps, photographs, personal letters and diaries, Navigating the Congo is an exhibition which explores the history of non-conformist involvement in the Congo River regions during the 19th and 20th century.

By looking at the collections held in The Angus Library and Archive, the exhibition seeks to bring to light some of the challenges faced in navigating this history and the relationships that developed between Baptist missionaries and the Kongo people during the period of European colonialism.

Two free talks will be held during the exhibition:

Tues 22nd Sept – Bandi Mbubi (Congo Calling) will be speaking on conflict in the DRC and fair trade technology

Thurs 24th Sept – Dr Rob Burroughs (Leeds Beckett University) will be speaking on Protestant missionary travellers in the Congo Free State

Bandi Mbubi is a founder and director of Congo Calling, an organisation who are working to bring the world’s attention to the atrocities being committed in the Congo and for a peaceful resolution to the ongoing war. Bandi writes and speaks nationally and internationally to create a mass movement of consumers who demand the development of fair trade technology which uses ethically-sourced, conflict-free minerals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Dr Rob Burroughs is Senior Lecturer in the School of Cultural Studies and Humanities, Leeds Beckett University. His publications include Travel Writing and Atrocities (Routledge 2011) and The Suppression of the Atlantic Slave Trade (co-edited with Richard Huzzey, Manchester 2015). Rob is the lead UK partner in the NWO-funded European research project ‘The Congo Free State across Languages, Media and Cultures’. Current projects include research of the Africans who testified against colonial violence in the Congo Free State.

For more information about our upcoming and past exhibitions visit our Exhibitions page

Categories: ExhibitionsDiscovering the treasures

Posted Friday, 14th August 2015

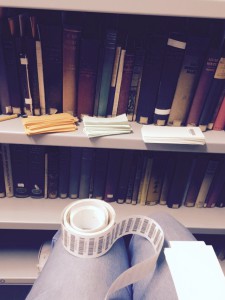

August is a somewhat strange month here at the Angus. We are closed to the public for the month which allows us time to get on with other jobs which are not that easy to perform when we have visitors. For example, I was able to do a stock take last week (using both of our large tables in the centre of the reading room!) and list some books for sale on Amazon.

Another task I have been enjoying very much this week is preparing some more books in the Angus archive for cataloguing. Our cataloguers, Lucy and Anna, have been doing an amazing job cataloguing everything (they’ve catalogued over 9,300 items since the start of the project) so in order to help speed up the process a bit, I have been inserting barcodes on little slips of card. I’ve also been identifying whether a book is pre-1830 (that get’s a little slip of green paper inserted into the book) or post-1830 (orange slip of paper). I think Lucy must have been inspired by Tic Tacs to choose those two colours…

Some might think this a rather odious task; after all we have lots and lots of books. Thousands of them in fact. And old books are dusty, and leave your clothes covered in a fine light brown powder (not to mention your hands). It has, though, been absolutely wonderful (and has been greatly assisted by the Beautiful South, Norah Jones and Radio 4 on occasion). Listening to the radio aside, it is all the little treasures that have been falling out of the books that have inspired me to write this blog post to you this afternoon and to share a few photos of them with you.

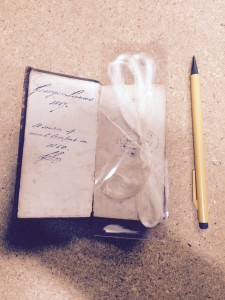

Here’s one of the first I inserted a barcode into. It’s a tiny little book called Meditations, complete with a lock of very fine blonde hair. The inscription made me well up…

There’s love poetry (not something you would perhaps expect in a Baptist library). This one was my favourite in this little book.

There’s something for those interested in the Clan Angus, a book printed by an Angus Watson and seems just circulated amongst friends and family.

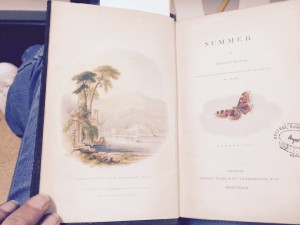

Some of the books have amazing illustrations, like these which are in books which have clearly been well used (their covers having fallen off at some point and now held on with binding tape) and probably well loved

There are some wonderful examples of illustrated Victorian/Edwardian book covers…

And some 17th and 18th century writing inside the first few pages…

Beyond a shadow of a doubt, my favourite find this week has been this (sorry the photo is so rubbish)

More discoveries will be shared next week…

Categories: UncategorizedHidden Treasures, part 3: In which the Lorrains encounter a fierce storm, a meteor and two hermits

Posted Tuesday, 11th August 2015

“It seems that we have been asleep but a few minutes when we hear the stentorian voice of our travelling companion shouting to the boatman to get up, & upon looking at our watch we find it already past five o’clock. There is the usual groaning among the men, the mumbling of inarticulate sentences & then again the startling shout “get up, get up” from our friend K-, repeated by his cook, his serving man & our boy who likes to feel that he has someone to order about. Presently the sound of the bubbling hookah is heard we know that the boatmen are taking their usual morning pull at the fragrant weed before turning out & unfastening the boats. A smell unknown to any but those who have travelled in the East pervades the atmosphere, it is the perfume given off by the smoking of a peculiar mixture of molasses & tobacco, in which all Bengalis revel, and which no doubt has a charm quite its own. The roof creaks & we know that one of the men has finished his humble breakfast & is walking over our heads in order to get to the front of the boat, & just as he is about to push the boat into the mainstream, the head of our boy Khuma appears in front of the dog kennel arrangement & then his hands come into view & we see that he is bringing us a cup of tea each before we start. We are soon shooting down the “long rapid” in fine style & all day long keep up at a fair speed, and as we are going with the stream there is little work for the men to do. We stop at midday for the men to take their food & we climb into K’s boat & sit under his “kennel”, native fashion on the floor & take our breakfast also, but we are nearly melted with the heat, the sun shining upon the mat roof so near to our heads making the boats almost unbearable & we are glad when we are once more moving for the rapid motion makes a cool breeze even in the warmest part of the day. When sunset comes we are glad to get off our backs where we have been lying all day & to stretch our limbs on a sandy beach, by running up and down & finally by taking a swim in the river. This gives us an appetite[d] for dinner & we do full justice to the goodly repast which is set before us. Soon after turning in, the heavens become overcast & the rumble of distant thunder warns us of the approach of a storm, amid the howling of the wind we hear K. giving orders to secure his boat & we see that ours is safely moored, the bamboo flap which serves as a door to our “kennel” is let down and tied, & presently the rain begins to fall in torrents, the whole air is full of the roar of thunder claps, groaning forest trees, & howling wind, & as we lie on our backs we can see through the numerous holes in our fragile door the almost incessant lightning flashes. The gentle rocking of our tiny craft upon the water serves however to sooth us and before long we are fast asleep, “rocked in the cradle of the deep”. The next thing we are conscious of is that the men are preparing to start & the day passes by quietly enough & at evening we tie up at Hermits’ Ghât. This is a rude landing place in the forest close to the hut of 2 hermits who are held in great veneration by all the boatmen who ply on this river. It is customary for every man to give these holy recluses some little token of respect as he passes, a few pice [sic], a pumpkin, a little salt or anything that happens to be handy. The old gentlemen who were here when we first came up the river have gone & their places have been taken by younger men – one a Hindoo & the other a Mahommedan. As we sit outside in the starlight – we amuse ourselves by watching the cooking operations of a Bengali, who being a good friend of the Hindoo caste, thinks that his food will be defiled if he cooks it on board the boat in which he is journeying, belonging as it does to Mussulmans, so he is sitting out in the open & in the darkness doing his best to prepare his evening meal, holding a lighted stick over the pot occasionally to see how his rice is cooking & between times fanning off the swarms of winged insects which seem intent upon precipitating themselves into his food. Suddenly our attention is arrested by a large meteor falling from the sky like a globe of fire & lightning up the darkness for one brief second. It appears to fall into the forest, a short distance from where we are seated, but doubtless our eyes have deceived us. We now think of turning in & the usual preparation of our beds takes place, & before long the only sounds which break the silence are those of the frogs on the shore & the insects in the surrounding jungle…”

Categories: Uncategorized

Recent Comments